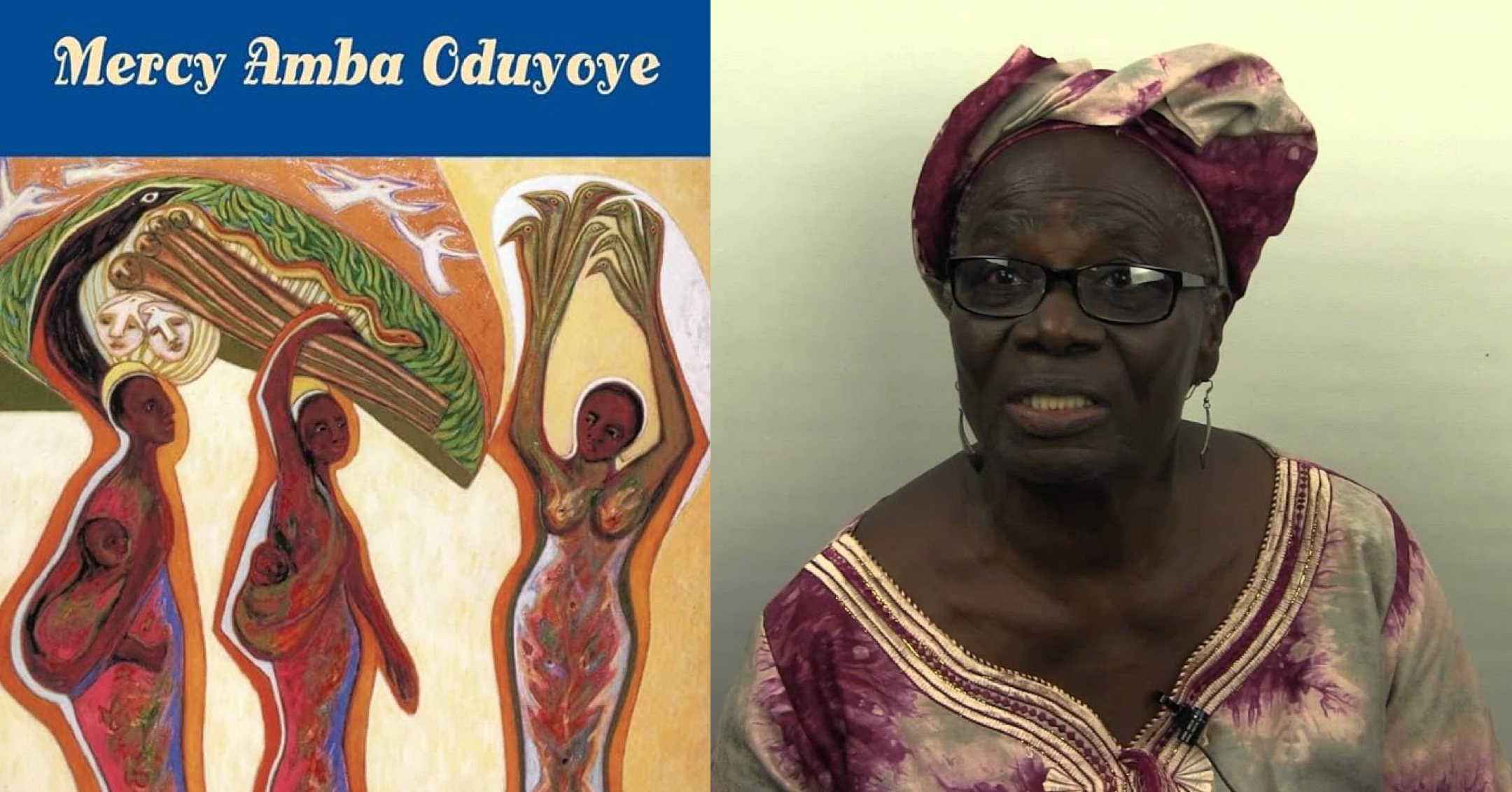

Theology should never be an abstract exercise. It must speak to life on the ground, to how faith is lived, not merely defined. Few have embodied that truth more fully than Mercy Amba Oduyoye, the Ghanaian theologian whose work has transformed the landscape of African Christian thought.

Her project is bold, speaking of God through the experiences of African women, to reclaim Christianity as a liberating rather than oppressive force, and to re-imagine the church as a community where all can belong. Her theology is a rare mix of courage and controversy, rich in wisdom, yet demanding careful discernment.

A Theology Born of Story

Oduyoye begins not in the study but in her own story. Raised in an Akan Methodist home, she grew up in a culture that honoured women in theory yet often sidelined them in practice. Her mother served faithfully in the church but received little recognition beside the men who preached. Out of that dissonance grew a theological question that shaped her life: Can the church that baptises women also silence them?

Her answer is found in what she calls “African women’s theology”, a faith that listens first to the voices history has ignored. In this sense, Oduyoye reclaims the incarnational instinct at the heart of Christianity that God meets humanity not in abstraction but in flesh and blood, in culture and circumstance.

The Strengths: Inclusion and Communion

Oduyoye’s insistence that African women’s voices are indispensable to theology is her greatest gift. Through the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians (founded in 1989), she created space for women across the continent to interpret Scripture in their own idiom and to claim their place within the Body of Christ.

It is theology “from below”, an echo of St Paul’s image in 1 Corinthians 12 with many members, one body. The Church, she argues, cannot be whole if half its members are mute.

Her vision also draws deeply from the African sense of community, what the Bantu call ubuntu, “I am because we are.” This emphasis on relational being aligns well with Anglican ecclesiology, which sees the Church as communion rather than mere institution. In that light, Oduyoye’s theology is not only feminist but profoundly catholic, restoring the wholeness of the people of God.

And, unlike some Western strands of feminist thought, hers is not combative. She critiques patriarchy without rejecting men, challenges the Church without abandoning it. It is theology as reconciliation, not revolt.

The Cautions: Experience and Orthodoxy

However the strengths of her method also reveal its vulnerabilities.

First, experience becomes her primary source of theology. While Anglicanism values experience, revelation in Christ must remain the starting point of theology. If human experience defines truth rather than illuminates it, theology risks becoming anthropology, a study of ourselves rather than of God.

Secondly, Oduyoye’s re-imagining of God in feminine terms, though a necessary corrective to patriarchal distortion, needs theological balance. Scripture indeed contains motherly imagery for God, but metaphor must never harden into ideology. The biblical instinct is complementarity, not replacement, Father and Mother, Lion and Lamb, justice and mercy held in tension.

Finally, her ecumenical generosity sometimes leans toward a blurred pluralism. In seeking to hear “all voices,” the distinct confession that Jesus Christ is Lord can become muted. Dialogue must enrich faith, not dissolve it.

An Anglican African Reading

For the Anglican Church in Africa, Oduyoye’s theology is both gift and provocation. It calls us to embody the Gospel’s radical inclusivity while remaining anchored in creedal truth.

Anglicanism’s genius has always been its both-and: Scripture and reason, faith and works, order and openness. Oduyoye presses us to add gender and justice to that list, not as political causes, but as theological necessities.

She also challenges the intellectual dependency of African Christianity. The Church must no longer borrow its theology from Europe; it must think, pray, and teach in its own voice. In that sense, Oduyoye’s project is deeply incarnational, the Word made flesh in African form.

Conclusion: Truth with a Human Face

Oduyoye’s theology is not flawless, few serious theologies are. But it has moral weight and spiritual integrity. It reminds us that doctrine without compassion is lifeless, and that the Gospel, if it is truly Gospel, must be good news for the woman at the well as much as for the priest at the altar.

Oduyoye brings theology back to the “ground truth.” She listens to the voices on the front line, mothers, daughters, market traders, midwives, and asks whether the Church’s strategy still serves its mission.

Her challenge to African Anglicanism is clear, theology must include the female voices in the church. This is particularly important across Africa, where women make up such a large proportion for the congregations, if not the leadership. If our faith cannot speak hope to those at the margins, then it has lost sight of the Christ who came from the margins himself.

In that sense, Mercy Amba Oduyoye stands as both prophet and pastor, calling the Church not to abandon orthodoxy, but to live it more faithfully. And that, in any language, is theology worth hearing.

Leave a Reply