The Gospel never changes, but the world it enters always does.

Every generation and every culture hears the Word of God through its own language, symbols, and stories. The challenge for the Church has always been to speak truthfully in ways people can understand. That is the heart of contextualisation. It is not about watering down the Gospel. It is about making sure that the message of Christ takes root in the soil where it is planted.

For the African Church, this is not a secondary task. It is central to mission and discipleship. The future of faith across the continent depends on our ability to speak the unchanging truth of Scripture in forms that reach the heart of African realities, in music, language, art, and community life.

What Contextualisation Really Means

Contextualisation begins with God Himself. The Word became flesh and lived among us. Jesus did not shout from heaven; He entered a particular time, culture, and place. He learned human language, human custom, and human need. The Incarnation is the first and greatest act of contextualisation.

The same principle shapes mission today. To communicate the Gospel well, we must understand both the world of the Bible and the world of our hearers. Mission is a bridge between these worlds. It requires listening as much as speaking.

Contextualisation does not mean altering the Gospel to make it acceptable. It means translating its meaning into the thought-forms and life-patterns of the hearer. It is faithfulness in local language.

Understanding the Cultures We Serve

Every culture has its own way of thinking about right and wrong, belonging and power. The Gospel addresses them all.

Some cultures are shaped by ideas of guilt and innocence, where wrongdoing is understood in legal terms, and people long for forgiveness. Others live by shame and honour, where belonging and respect are central, and the deepest wound is rejection. Still others think in terms of fear and power, where life is lived in relationship to spiritual forces, and people seek safety and authority through ritual or protection.

Africa knows these layers well. In many communities, honour and shame shape relationships, while the reality of spiritual power and fear remains close to daily life. The Gospel must speak to these dimensions, not only to guilt and forgiveness, but to freedom, dignity, and victory in Christ. When Jesus heals the sick, forgives the sinner, restores the outcast, and defeats the demonic, He addresses all three worldviews in one redeeming act.

When the Church Learns to Listen

Much damage has been done when Christianity has arrived wearing foreign clothes. During the colonial era, the Gospel was sometimes tied to Western power and culture. Churches built on that foundation often struggled to express the faith in truly local ways. Faith risked being seen as imported rather than indigenous.

Contextualisation calls the Church to recover humility, to listen to the wisdom of the people it serves. It means honouring local language, valuing local art, and trusting that the Holy Spirit is already at work within the culture. It also means having the courage to name what must change, for every culture carries both grace and sin.

When the Church listens well, it begins to see how the Gospel answers the deep questions already present in people’s hearts. The African sense of community, respect for elders, and awareness of the spiritual world can become doors through which the truth of Christ shines.

Faithful Translation, Not Cultural Surrender

There is always a tension here. Contextualisation must not slip into compromise. The Church cannot baptise cultural practices that deny the Gospel’s moral truth. Yet nor should it reject everything that feels unfamiliar.

The task is to discern. Every culture carries echoes of God’s image, longings for justice, belonging, and power rightly ordered. These longings find their fulfilment in Christ. The Church’s role is to connect those echoes to the true story of redemption.

A faithful Church does not copy foreign models nor retreat into isolation. It learns to express the same Gospel through local voices, African prayers, African rhythms, African thought. This is not syncretism; it is incarnation.

The Missionary’s Posture

The missionary or church leader must therefore be a learner before being a teacher. True contextualisation begins with humility. Those who carry the Gospel are not its source; they are its servants.

As one model puts it, we move between three cultures, the world of the Bible, our own culture, and the culture of those we seek to reach. To cross that bridge requires patience, prayer, and love. The goal is not to make converts to our way of life but disciples of Jesus who live out their faith within their own culture.

When local believers become the interpreters of Scripture for their own communities, the Gospel ceases to sound foreign. It becomes homegrown and that is when faith flourishes.

Why Contextualisation Matters for the African Church

The African Church is now one of the great centres of global Christianity. Yet growth brings responsibility. Our theology, our worship, and our witness must be both rooted in Scripture and responsive to African realities.

Contextualisation enables the Gospel to speak to the pain of conflict, the scars of poverty, the power of community, and the hope of renewal. It allows the Church to confront corruption and tribalism with biblical truth, to address spiritual fear with the victory of Christ, and to affirm human dignity in the face of exploitation.

It also strengthens mission. A contextual church sends missionaries who understand how to listen, adapt, and translate the Gospel in other cultures. The next great wave of world mission will come from Africa, and it will succeed only if it is both faithful to the Word and fluent in the world.

Conclusion

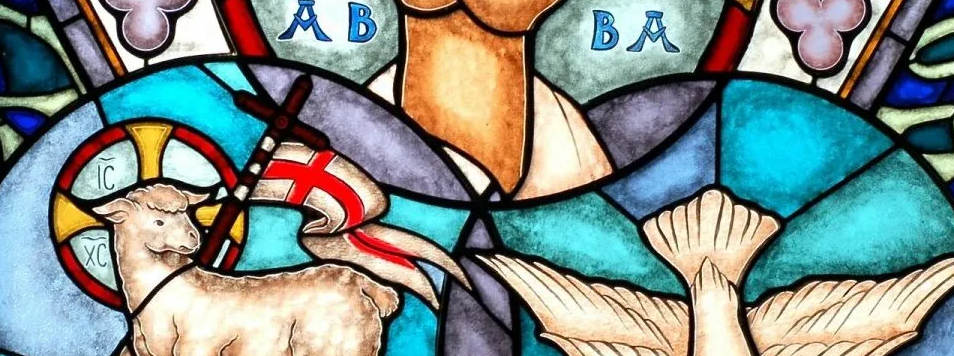

Contextualisation is not a modern invention. It is how the Church has always grown. The Gospel took Greek words in the first century, Latin logic in the fourth, and African melody in the twenty-first. Each culture, touched by Christ, reflects His glory in its own way.

For African Anglicans, this is both opportunity and calling. The Church must keep Scripture at its centre while speaking in the languages and patterns of its people. The message remains the same: Jesus Christ, crucified and risen. But the form of that message, the way it is sung, prayed, and lived, must be truly our own.

When the Church learns to do this well, the Gospel does not lose its power. It gains its voice.

Leave a Reply