Introduction

Let’s be clear from the start. Liturgy is not decoration. It is the way the Church allows Scripture to speak, shape, and steady our common life. Through confession, proclamation, and sacrament, the liturgy turns the Bible into a rhythm we live by. It gathers us into the story of God’s redeeming work and forms us into a praying, learning, and serving community.

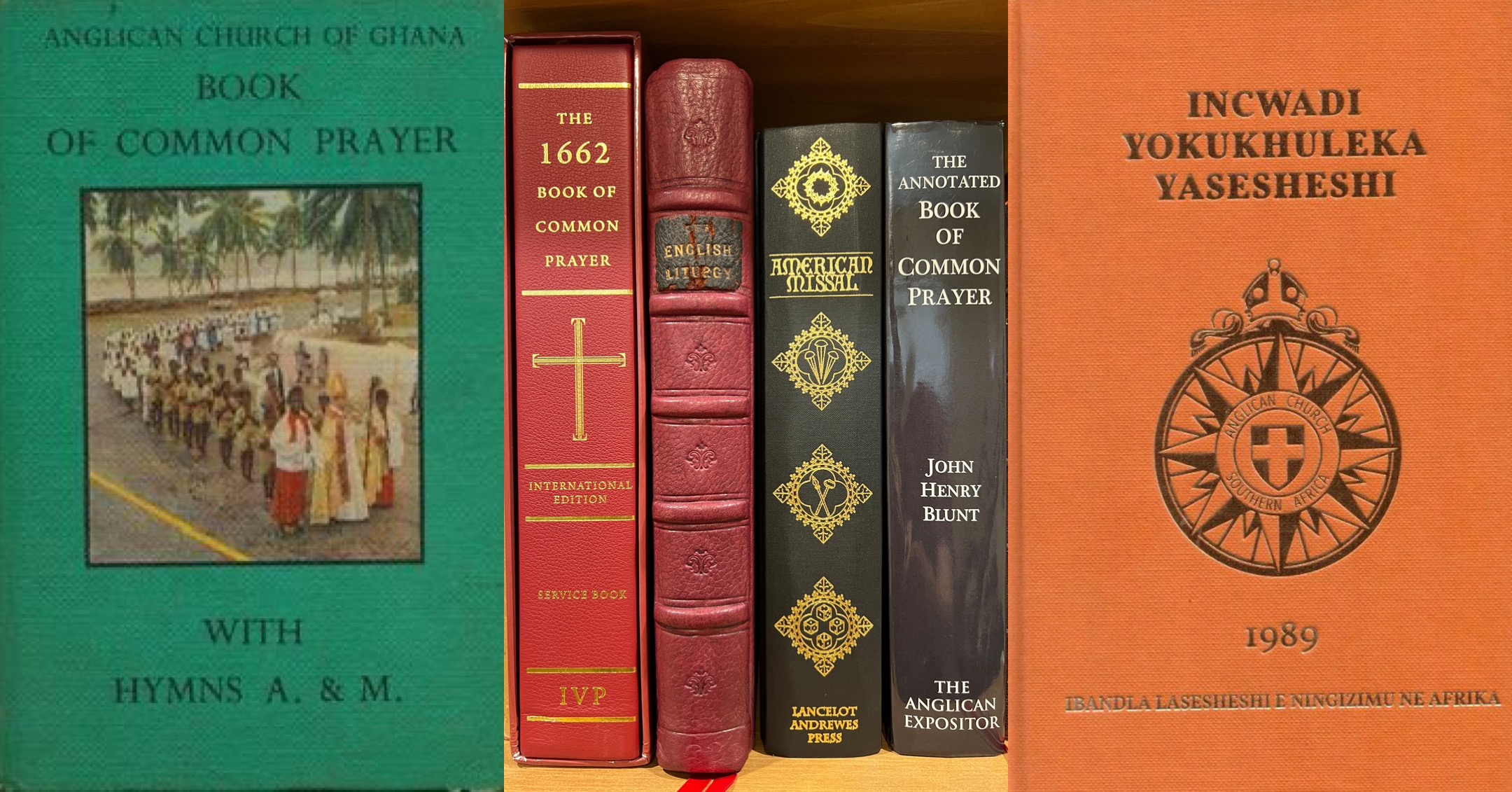

For Anglicans in Africa, this heritage carries deep meaning. Our liturgy may have taken shape in England, but its roots reach much further back, into the wisdom of the early African Church. Some of the greatest minds in Christian history were African. They helped the whole Church learn how to pray, how to believe, and how to live faithfully in difficult times.

1. The Bible at the Centre of Worship

Anglican liturgy is thoroughly biblical. Every prayer and response in the Book of Common Prayer carries the language and thought of Scripture. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer’s vision was simple but profound: to let the whole Bible be prayed by the whole Church in the language of ordinary people.

The ECSS Handbook puts it well: the Prayer Book “transforms the Holy Scriptures into a Rule of Life.” In other words, we are not just reciting words; we are being shaped by them. The steady rhythm of confession, praise, and thanksgiving teaches us what it means to be disciples.

When churches drift away from this rhythm, they often lose that slow, steady formation that turns faith into character. Preaching remains vital, of course, but preaching alone cannot form a praying people. Scripture must be woven through the worship of the Church if we are to grow in grace and truth.

2. The African Roots of Anglicanism

Although Anglicanism was shaped in England, its theological foundations were laid long before, by the African fathers of the early Church.

- Tertullian of Carthage gave us the very word “Trinity” and helped the Church speak rightly about Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

- Cyprian of Carthage taught about the unity of the Church, the ministry of bishops, and the discipline of prayer.

- Augustine of Hippo explored grace, sin, and salvation, themes that later guided the English Reformers and deeply influenced Cranmer himself.

When Cranmer and his colleagues reformed the Church’s worship in the sixteenth century, they were not trying to invent something new. They were reaching back to this ancient wisdom. Their aim was to restore the simplicity and devotion of the early Church, much of which had been forged in Africa.

In that sense, Anglicanism is both catholic and reformed. It holds fast to the faith of the ancient Church while expressing it in the clear and scriptural language of the people.

3. Contextual Worship for a Living Church

From the first American Prayer Books after independence to the many African revisions after decolonisation, Anglicans have continually adapted their worship to local settings. In Africa, we have translated the liturgy into our own languages, sung it with our own rhythms, and prayed it in our own contexts.

That process is not a betrayal of the past but a continuation of it. Contextualisation ensures that the Gospel speaks to people where they are. Yet it must always be faithful to what the Gospel actually says.

Faithful contextualisation means we can change the form without changing the faith. We can express ancient truths in new words without altering the truths themselves. So when churches rephrase certain metaphors or expand language to be more inclusive, they must still affirm what is unchanging:

- One God in three Persons

- Salvation through Christ alone

- The authority of Holy Scripture

- The call to grace, repentance, and forgiveness

The task, then, is to remain doctrinally faithful and contextually relevant. The message does not change, but the voice through which it is spoken can and should reflect the people God has called to worship Him.

4. The Core That Unites Us

Whatever shape Anglican worship takes, certain things must remain at the centre:

- Scripture and preaching, the Word of God proclaimed to His people

- Confession and forgiveness, the gift of grace renewed

- The Creeds, the public confession of the faith once delivered

- The Eucharist, the sacrament that unites us in Christ

- Intercession and blessing, the sending out of the Church in service

These elements hold us together across cultures and centuries. They ensure that our worship remains recognisably Christian and biblically grounded, even as its form reflects the diversity of God’s world.

5. Why Liturgy Still Matters

Liturgy is not a museum piece. It is a living discipline of the Church, a pattern that teaches us how to pray, how to confess, how to give thanks, and how to trust God. When we pray the Scriptures together, our hearts are shaped in humility, reverence, and joy.

Churches that abandon this pattern often lose the anchor that holds worship steady. But when Word and Sacrament remain central, the Church grows deep in faith and wide in love. It becomes both rooted and alive, both ancient and new.

Conclusion

Anglican liturgical worship is both ancient and alive. It is biblical in its content, African in its heritage, and global in its reach. It connects today’s congregations to the wisdom of the early Church, many of whose greatest teachers were African, while allowing every province to express that same faith in its own voice.

The task before the Anglican Church in Africa is not to discard tradition but to renew it. We are called to keep the liturgy doctrinally faithful and contextually relevant, so that every generation can worship the living God in spirit and in truth.

At its best, liturgy is Scripture prayed, the Gospel sung, and discipleship lived. It is the rhythm through which the Church is formed, equipped, and sent out for the mission of God in the world.

Leave a Reply